What PPC manufacturer would you recommend?

Obviously we’re not going to answer that question directly, but our experiences (good, bad, and horrible) have led us to look for a handful of things that will help you decide on a manufacturer that meets your needs.

- Shop like you would shop for a new car. Aircraft manufacturers don’t sell units in the massive quantities like car companies do. That means you should expect a similar or better level of courtesy, service, and support. Walk away if you don’t.

- What type of engine do you want? This has to be really thought about, because, of all the components on your PPC, this constitutes as much as 50+% of the aircraft’s cost, and it is what YOU will have to live with and maintain for the life of the aircraft. The aircraft manufacturer might fold shop and the frame may be solid, but that engine will need to be managed and maintained year after year. When we talk to PPC owners and ask what they their biggest complaint is about owning a specific PPC, it is nearly 100% related to the engine in some way. We don’t think anyone makes a bad engine, per se, but each one has its quirks.

- Consider the level of manufacturer support you’ll need. Some folks can buy a unit and never need to talk to the manufacturer again, while others have less mechanical and technical skill, and may lean on their manufacturer more heavily. If you’re in that latter category, or a manufacturer requires you to physically bring the unit back to them whenever it needs work, they won’t be desirable if they reside on the opposite side of the country. This isn’t a common concern, but it’s still something to think about. Remember that engine support can often be obtained from many other sources (including the engine manufacturer themselves), so you might want to separate that out from this particular decision.

- Visit a PPC fly-in… talk to owners, and take a look at the units that have been flying for a couple of years. Some units may look good rolling off the floor, but they might experience wear, fatigue, and need maintenance/repair/replacements sooner than you expected.

- What’s their WRITTEN warranty? We’ve had top-tier manufacturers effectively tell us ‘we don’t warranty anything, except any warranties that carry over from some of our component suppliers‘, while we’ve seen small builders guarantee the craftsmanship on the whole unit for multiple years. Don’t let an aircraft manufacturer trick you into thinking they’re special, exempt, or that the ‘experimental’ in ELSA is a get-out-of-jail-free card for them. If you can successfully sue a bungee cord company for a poke in the eye, we think an aircraft manufacturer is probably going to have to own up to some level of accountability.

Remember that they are just manufacturers, which means they produce a product and should take some level of responsibility for the quality of its construction, at least for the first year or so. Unfortunately many PPC manufacturers are – ironically – not ran by people with the best business sense (which is probably why they seem to come and go so often). If you find a good one, reward them with a purchase. - Ask what they’d do if a component failed, and you believe it was attributed to a design or construction issue. Of course it’s a provocative question, but it will help you find out what they’re really like. When everything is going right, everyone is happy. The bigger question is – how do they behave when something goes WRONG? We’ve asked this question of several manufacturers… Curses. Threats. Personal attacks and insults. They were equal parts sad, fascinating, and enlightening to watch/hear.

This particular ‘shopping test’ was originally inspired by one of our brethren who contacted their PPC’s manufacturer to highlight a concern about safety related to what they believed was the premature failure of a part (they were not asking for anything, just advising of what happened). The response was an attack e-mail in which the owner was told that they [the manufacturer] had zero liability no matter what happened, the pilot is ALWAYS at fault for anything bad that might happen in their PPC anyways, and that if that owner didn’t want to ‘accept the risk of flying, they should sell their PPC to someone who does‘. All we could say: Wow. On that note, you can see why we think it’s important to discover those kinds of attitudes up front, before you’re stuck with someone like that!

That about covers it. We know that might have seemed like a weird list, but consider that most PPCs can be tweaked over time with different canopies, props, radios, seats, seatbelts, wheels, brakes, lights, etc., there’s a lot of room post-manufacturer to customize a lot of the other attributes of a PPC to your liking later (unless it’s an SLSA).

Have any other purchasing suggestions? Let us know.

What should I be looking for when purchasing a trailer for my PPC?

Some PPC manufacturers will try to sell you a trailer along with the unit. Sometimes it can be a good deal, but sometimes it is lost money.

Let’s focus on the upscale purchase, since flatbed trailers are pretty self-explanatory. If we consider an enclosed trailer holding the biggest 2-seat units (the Powrachute Airwolf apparently holds that distinction as of this writing), you’re going to need a minimum open floor space of 121” long by 81” wide between the wheel wells, and a minimum rear door opening height of 92” to fully clear the prop ring. Realize that, if you opt for the cheaper traditional/off-the-shelf door height, you’ll have to tip the unit back or build a special loading ramp to clear the prop ring every time you load and unload it, which is a pain, and especially if you are considering using a winch to assist in loading operations.

Beyond that, the trailer elements are up to you, and like PPC manufacturers we are loathe to specify one manufacturer over another. Ask around, look around. Don’t be pressured by the PPC manufacturer. Not all trailers are alike, and some trailer brands have much higher fit and finish than others. Get a list of all of the available options, because retrofitting may not be possible or will be more expensive later on. Trailers have to withstand the rigors of travel and function as a portable hanger, so you’ll want to make sure they are strong and reliable. This isn’t a place to be cheap, especially when it’s protecting a more expensive PPC variant.

A few other thoughts:

- What else will you want to haul? You would be surprised how many people will originally buy a trailer just big enough to squeeze in the PPC, but then inevitably upgrade to a longer unit (20’ or more) in just a year or two. The reason is that you realize, while traveling to that fly-in, you may also want to bring along your side-by-side, ATV, motorcycle, canoes/kayaks, camping gear, etc., not to mention fuel, spare parts, tools, etc. for maintaining the PPC itself.

- Light vs. heavy-duty. If you want to put your Jeep in with the PPC, you’ll want to aim for the 10,000 lb or higher frame and axles. Some PPC manufacturers will tell you a light duty trailer is fine and that a heavy-duty trailer will ‘ride rough’, but it’s garbage. Besides, they don’t have to live with the trailer, you do. A heavy-duty trailer often costs nominally more, and gives you the flexibility to change your mind about how you’ll use it later on. Besides, if you really feel like you need to soften the ride, you can always ‘downgrade’ the trailer with softer springs/axles… the opposite isn’t true, because the lighter gauge frame is still the weak point, even with stronger axles.

- Install a quality weight distribution and anti-sway hitch. These trailers are tall, even when pulled behind a motorhome, and highly susceptible to the frontal wind and side gusts. Despite whatever a manufacturer might say about the trailer’s stability, the use of an anti-sway hitch system is strongly recommended. Because these trailers are typically lighter weight, a lighter and easier-to-use system like the chain-based Andersen ‘No-Sway’ Weight Distribution Hitch can be considered.

- Consider investing in E-track installation, at least on the floors. A worthwhile investment on a new trailer, it makes tying down the PPC and other cargo much easier and more flexible. Most trailers will come from the factory with a handful of D-rings (at best), but everyone here agrees it is guaranteed you’ll be adding more later. We believe the investment is worth it: ask for a pair of full-length runs of E-track spaced 4′ apart (they’ll then lay the floor plywood right between them), and be sure they are welded to each of the frame members. Not only do you get much stronger connection points, but the track itself acts as an additional framing brace, actually making your trailer stronger.

- Make sure to get spares for the trailer. Good options include a spare tire (or two) and a spare wheel hub with pre-installed bearings. Have you ever tried finding and replacing wheel bearings on the side of an interstate? Not fun. Nothing is worse than being stranded on the side of a road knowing that a measly $200 or less in spare parts could have saved the day (or days, depending on the availability of those parts).

- Get some x-chocks. If you’re traveling with your trailer extensively, invest in a pair of X-chocks (they fit and tighten between the two tires on each side to secure trailer movement in either direction). Experience shows that they’re vital when something to physically chock behind the tires isn’t available, and they’re absolutely CRITICAL if you’re trying to chock the tires in loose dirt/gravel where traditional ground chocks just don’t work (you know… like those fields and grass airstrips where you’ll fly).

- Level your trailer before towing. The number one reason we see people with flat tires on the side of the road is because they failed to properly level the trailer. The Andersen hitch mentioned above will make this a breeze, but if you go with something else, be sure to use an appropriately sized drop hitch. If too low, the trailer will sway too much, but if it is too high (more common) you effectively end up running the trailer on just the rear set of wheels and all of the weight is borne by one axle, which inevitably overloads, overheats, and causes something to fail.

One last thing: will the PPC manufacturer make you bring your own straps, tie downs, or e-track clips? We’ve seen where they provided the trailer and PPC… and NOTHING else, bizarrely sending their customer scrambling off to a hardware store to buy clips and straps that would’ve cost less than $20, but they were too cheap to include. We have our opinions about those kind of folks, but setting that aside… it’s at least better to know up front than to have them RUIN what should be an otherwise exciting/happy moment of getting your new aircraft. Short story: confirm what they are providing, what they are not, and plan ahead.

I‘ve been told that, "The Pilot in Command (PIC) is always at fault." That doesn’t seem right... is that really true? Position

There are several moving parts to this question, so bear with this response.

The PIC, Then and Now

Pilots screw up… a lot. There are many, many dumb things a pilots can do. It is not unreasonable to suggest NTSB investigative records are a regular encyclopedia of human stupidity. Statistically, as much as 80% of all general aviation accidents in the United States are attributable to pilots making bad choices. (Note that investigators officially now carefully avoid the term ‘pilot error’, as it creates a false set of impressions about the reality, which we’ll allude to shortly).

Are PPC pilots any better? Obviously no, but we’re also a little unique: as one of the more recently aircraft technologies in aviation history, the PPC flying culture is still one of the youngest and maturing. Today’s PPC Sport Pilot is expected to pass tests, acquire training and experience, get licensed, have a minimum level of medical stability, and take responsibility for ensuring (and documenting) the airworthiness and maintenance of our aircraft. PPC Sport Pilots have heightened and predominant responsibilities for a safe PPC flight, and must understand the risks. If you have not already done so, read the FAA Risk Management Handbook (FAA-H-8083-2).

So we acknowledge that pilots are indeed at fault a lot, but we’re always trying to get better. Well, at least… SOME of us are.

Likely Origins of the Mindset

OK, we are going to make a broad and semi-crude generalization now: ultralight PPC pilots and their PPG cousins on average have a much more ‘liberal’ interpretation of what constitutes safe flying. Of course there are good, safe pilots in those categories, but as a group…? As we have differentiated elsewhere on this site, there is effectively no formal oversight of ultralight aircraft, equipment, or pilots. Let that sink in. Today, even remote pilots for little drones/UAVs have to get trained and licensed! This means that, other than staying within FAA weight and airspace limitations, this group can effectively do whatever it wants. More importantly, for most of them they operate in that environment because they like it that way.

That’s an extended backstory to thus suggesting that we suspect ultralight PPC and PPG pilots are the ‘origin’ of the mindset, where there is still a home for people who specifically revel in trying out new ideas, pushing limits, taking risks, breaking rules, breaking things, breaking their equipment and themselves, etc.

“You built the crazy thing and hopped into it, so whether it flies or dies, it’s your problem.” If you’ve heard this kind of notional, its because that is in fact significant chunk of their flying environment and reality. But it doesn’t reflect the realities of most of modern aviation.

Now we want to look at the real world where risk management is more reasonably and actually applied, and disagree with the statement.

Pilots as 1/3 of the Problem

We disagree with the statement because we don’t believe that it accurately reflects or applies a comprehensive risk management process, and it is time that attitudes change. The reality is that flying a PPC is a combination of man and machine influenced by many factors, both controllable and uncontrollable. We believe that pilots and the aircraft manufacturers (when appropriate) should accept their respective roles and accountability in the industry. Just because 80% of accidents can be attributed to the pilot, it still doesn’t mean that the pilot is 80-100% at fault in those instances, while also leaving 20% of accidents that are in fact primarily attributable to something else altogether as a given. If you’re interested in the legal side of this, you might wish to search on ‘comparative negligence’ as a primer for this subject.

The statement in question is really about assigning fault, so it assumes something has gone wrong and there is a desire to apportion blame. Thusly, there are really three possible contributors that would be considered:

- The decision-making of the pilot

- The design and reliability of the aircraft

- Unknown or uncontrollable external forces at work

A pilot who chooses to fly on a windy, gusty day is purposefully engaging in extremely heightened, risky behavior. A quick sanity check against the idea that there is no such thing as an emergency take-off will demonstrate that. If the pilot chooses to put themselves in obviously risky situations, that is truly the fault of the PIC.

On the other hand, a pilot who does everything ‘right’ (including regular maintenance) but has a sudden catastrophic engine failure mid-flight is a lot harder to blame. The pilot may have been neglecting to do maintenance, but maybe not. Rather, we might find that the engine has a history of such failures, but the manufacturer has been silent to advising of the fix (or paying the costs to resolve the problem). Or maybe there’s an obvious design problem that will naturally affect pilots of a certain weight/height. Design faults are actually exceedingly common in commercial aircraft… so why would we not expect them to appear in our own neck of the woods?

The last bullet precludes being able to actually ‘blame’ something. Micro-bursts on an otherwise-calm day have swatted aircraft from the skies like flies without warning. Hardware failures that would have been undetectable (short of tearing the aircraft apart to every nut and bolt) have killed hundreds in a second. Military actions have shot down innocent pilots, and idiots with laser pointers have blinded others while trying to land. None of these represent a failure of the pilot or the aircraft, and yet they happen with measurable frequency.

Balancing Pilot and Manufacturer Responsibilities

In short, the highly questionable statement assumes that the pilot can control or mitigate all of the risks. Aside from simply being a stupid argument, it’s more technically a first-degree violation of basic risk management practices. Generalizing again, we’re inclined to suspect you’d hear it from one of those ‘Wild West’ holdovers, where it’s every man for himself in the air, and each person ‘holds their own cards’. They’re completely oblivious to the fact that playing cards is STILL a game of chance.

Based on input from many new and old pilots alike, the consensus is that flying around people who think like this can be terrifying. While it defies logic, they extend the philosophy to assume that because everyone is responsible to look out for themselves, that means that they can do any crazy thing they want and folks will get out of their way. Feel free to disagree with us, but we’ve been there.

On the manufacturer side, the problem is that the ability of a pilot to fully recognize or address potential engineering problems diminishes as aircraft (including PPCs) become more and more complex in design and engineering. Yes, we completely agree with today’s PPC manufacturers who market and argue that costs have gone up because there is an increasing amount of design, engineering, and construction complexity that goes into the modern PPC. But there is also the corollary to that, which says that the PIC/aircraft owner/maintainer must therefore also increasingly and necessarily rely on the manufacturer to get things right during that process… and acknowledge when there are problems after-the-fact.

There are still manufacturers (or at least their representatives) who believe they have the right to just ‘throw that PPC over the fence’, and it’s your problem now. They think their liability is zero, and aside from being legally indefensible, it’s also unethical and plain wrong. This must change. We don’t accept ‘Wild West’ flying from licensed pilots, and we shouldn’t accept ‘not-our-problem’ construction and support from PPC manufacturers.

Consider the events of the Boeing 737 MAX MCAS debacle. If your spouse or child died in one of those aircraft where the autopilot software and sensors effectively malfunctioned to fly the aircraft into the ground, would you (or are you) suggesting Boeing has no liability? Do you really believe the pilots were 100% at fault? If it was 100% the pilots’ fault, why did we ground the planes? Why didn’t the pilot just ‘work around’ the aircraft’s deficiency or ground the aircraft themselves? It’s a nonsensical suggestion.

So we affirm: A PPC manufacturer is and should NEVER be held harmless when it comes to their failures to: recognize, test for, and openly acknowledge deficiencies of their designs, construction techniques, or specific aircraft assemblies; recommend fixes or other mitigations; and/or actively provide corrections for such deficiencies. If PPC pilots have matured, why haven’t the PPC manufacturers? Why don’t we expect the same (or higher) standards from the companies and people that build the equipment we use? Note we’re not arguing that the aircraft is perfect from the factory, but when they find a flaw or issue they need to let people know. Even if the fix has to be done out of our own pockets, at least we as aircraft owners will know what needs to be done.

For the PPC manufacturer who continues to maintain that attitude, its days are, frankly, numbered… just ask Boeing how much their mistake has cost them, and they have much deeper pockets than a PPC business. Around here, we politely suggest pilots look elsewhere for an aircraft if they encounter the ‘not-our-problem’ attitude. And with no cynicism implied, we honestly hope that – despite that attitude – those manufacturers have adequately insured their company when they are inevitably sued. It’s not that we care about the business owners in those scenarios, but we always hate to see good employees lose their jobs as the result of arrogance and short-sighted leadership.

Can I laminate my Airworthiness Certificate?

You’ll be unsurprised to know that we are adverse to promising anything surrounding what the FAA ‘thinks’ or ‘allows’, and you must always verify what the latest and greatest orders, directives, and legal interpretations are from the FAA… but right now the answer appears to be YES, you can.

The July 21, 2017 version of FAA Order 8130.2J contains an Appendix A, which provides directives and guidance to FAA inspectors and other representatives on how to prepare Form 8100-2, otherwise known as the Standard Airworthiness Certificate. Rather than us restating it, take a look for yourself (from the top of the page):

(https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/orders_notices/index.cfm/go/document.information/documentid/1031547)

(https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/orders_notices/index.cfm/go/document.information/documentid/1031547)

As you can see, FAA representatives are actually supposed to encourage you to protect the document… not just allow it. I would imagine that the same logic can be extended to your signed copy of the aircraft’s registration, although the fact that it has an expiration and gets replaced every few years may not make it worth the hassle.

Now, if you have a Special Airworthiness Certificate (which most of us do) you can still laminate it (which we personally affirmed with our own respective FAA representatives), but this means that we might now be talking about several full letter-size pages. To remain compliant with 8130.2 rules, each page must be laminated separately and then ‘attached’ together. Options to join them together can include traditional stapling (which makes two tiny holes in the paper) or perhaps use a key chain ring through a small hole – that does not obscure any of the form text – in each laminated corner (just a slightly larger hole than the staple).

As a final note, having a backup copy of your paperwork will generally get you past most inspections in the interim, even if the originals are damaged or lost. Thus, we would always encourage you to have another readable copy of all of your aircraft’s key documents stashed somewhere safe off of the aircraft, regardless of whether you laminate the originals or not. We have yet to meet a person who regularly looks forward to making a visit to their FSDO, so a little planning can go a long way.

What kind of tires should be used on a PPC?

So, honestly, we wouldn’t normally consider this a typical FAQ inclusion, except it has been asked so many times we finally felt it deserved our two cents’ worth.

The short answer is that there is not an absolute right or wrong tire to use on a PPC, but we made a point of surveying a number of our community’s oldest and most experienced to see if we could at least get some clear preferences. And actually, there were.

The first attribute is one of width… skinny vs. wide.

Wide was especially important to people in the two extremes of runway conditions: those who fly on grass in rainy areas, and those flying in dry, soft, sandy areas. In both cases the width was important to keeping the units from sinking, and in some cases even preventing narrow tires from actually ‘cutting’ lines in the sod/sand. Those who flew almost exclusively on asphalt seemed like it didn’t matter to them, although a few pointed out that wider tires technically added a little extra weight, which might make a different for those trying to stay beneath the 254 pound FAR 103 limit.

Our verdict: Use the wider tires. You never know where you might fly next, and we’re too lazy to even consider changing out tires depending on flying locations or conditions.

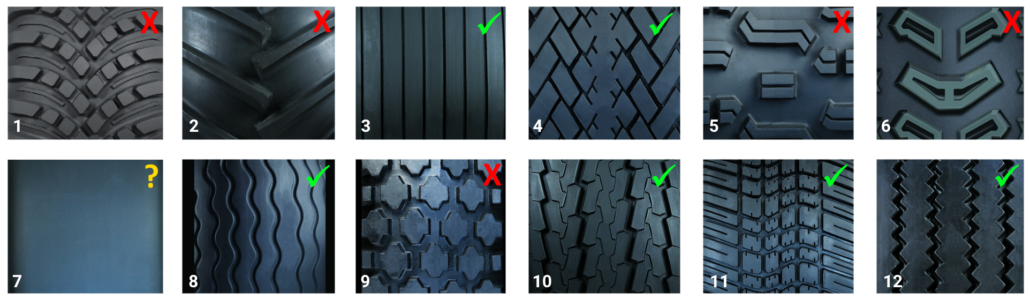

The other attribute for consideration is the tread pattern. We’re going to reference the image above.

There were a lot of theories that cropped up around this attribute, but there were a handful of experienced folks who argued a definitive exclusion, at least backed by their own history of observations: knobby tires are a no-go, regardless of runway conditions. The items above marked with the red X are examples of tire patterns to avoid. The reason is that, when attempting to land in less-than-ideal crosswind conditions (which we never do, right?), the canopy will try to pull the unit to the side. On grass/dirt/sand, folks have observed how units with knobby tires would grab the ground in a side slip and actually try to (or successfully) pivot/tip the unit over, while similar units landing at the same time on the same runway with flatter profiles would allow the unit to slip/slide a bit while the canopy settled itself. Our asphalt flyers interestingly agreed with the no knobby rule, although they highlighted the fact that they’re simply an annoying ride on hard surfaces, and that the knobs actually reduce the contact patch size on asphalt (just like any other vehicle).

Our verdict: Use flat-profiled tires (like the items above marked with the green check). We couldn’t really get anyone to highlight either benefits or downsides of slick/smooth tires, so they’re the only ones marked with a question mark. We don’t think they’re problematic per se, but we can see where – on wet grass or really soft sand (we’re think of you, Yuma flyers) – having no grabbing tread whatsoever can be less-than-ideal, too. Personally, we tend to like #3, #8, #11, and #12. Of course, if you go to a PPC fly-in or fly regularly with others, those choices won’t be much of a surprise.

How are PPCs supposed to identify themselves over the radio?

So, there are basically two answers to this, depending on where you are at.

If you’re making radio calls in a non-towered environment, just about anything will do that identifies you to your fellow pilots. We’ve even heard folks call out “This is Dave 1234F making a final…“, and it worked simply because everyone else who regularly flew in the area knew who ‘Dave’ was.

In a non-towered environment, there is no such things as bad radio communications. Anything you call out with reasonable accuracy will help to provide additional awareness about you and what you’re doing to others flying around you. Even a completely indiscernible message at least tells other pilots there is someone in the area to watch for.

Now, if you’re making radio calls in a towered environment, the proper identifier is ‘PARA’, regardless of PPC manufacturer. They lump us all together. This is spelled out in FAA Order 7360.1x: Aircraft Type Designators. (X is a placeholder letter that changes over time, as they regularly revise this particular document; it was ‘G’ as of mid-2022.)

Just to get a warm and fuzzy confirmation, we went and talked to a couple of different control towers. The not-so-warm-and-fuzzy result, though, was that a couple of controllers didn’t know what a PPC was (ouch), and several of the others suggested that – at least the first time – you fully identify yourself as ‘Powered Parachute’ just to give the tower a heads up. One even suggested that, once you’ve made initial contact, advise the tower in a second call of what your unit’s intrinsically slow and fixed airspeed is so they can route you/traffic accordingly and don’t accidentally drop you in the high-speed pattern.

Our advice:

- If you fly where there are other PPCs regularly, a call of ‘PARA’ or ‘PPC’ is probably adequate; you might add your obvious chute color if you need to distinguish yourself from the crowd (e.g., ‘Blue PPC’).

- If you fly into an airport (any type) not familiar with PPC traffic, make the first call the full descriptor of ‘Powered Parachute’. Thereafter, go with #1 at non-towered, or the official ‘PARA’ at towered airports.

- If you intend to fly regularly at a towered airport, visit the controller tower before hand and introduce yourself. Be prepared in-advance with a video of what a PPC is, and where the aircraft type exists in the FAR (seriously).